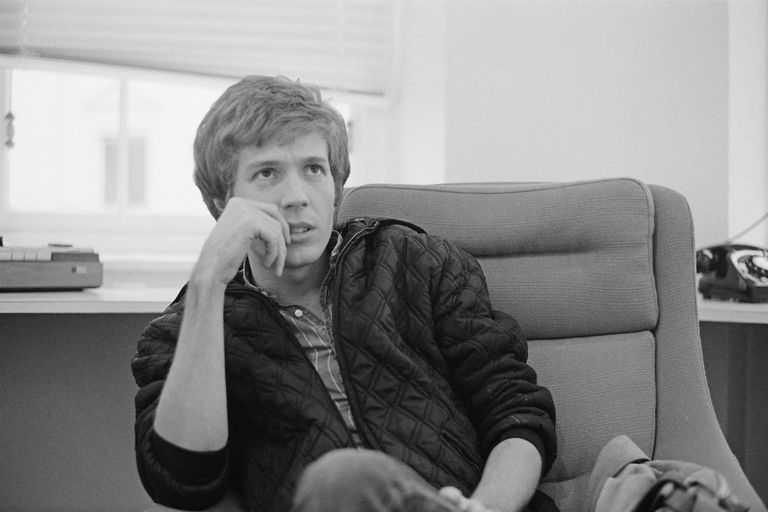

Scott Walker was born Noel Scott Engel (January 9, 1943 – March 22, 2019) and was an American-born English singer-songwriter, composer and record producer. He was known for his distinctive baritone voice and an unorthodox career path which took him from 1960s teen pop icon to 21st-century avant-garde musician. Scott Walker’s success was largely in the United Kingdom, where his first three solo albums reached the top ten, and where he lived from 1965 and became a UK citizen in 1970.

Noel Scott Engel was born in Hamilton, Ohio, US, the son of Elizabeth Marie (Fortier), who was from Montreal, Quebec, Canada, and Noel Walter Engel. Scott and his mother eventually settled in California in 1959.

At the time of his arrival in Los Angeles, Scott had already become interested in the progressive jazz of Stan Kenton and Bill Evans, he was also a self-confessed “Continental suit-wearing natural enemy of the Californian surfer” and a fan of European cinema (in particular Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini and Robert Bresson) and the Beat poets. In between attending art school and furthering his interests in cinema and literature, Scott played bass guitar and was proficient enough to get session work as a teenager.

In 1961, after playing with the Routers, he met guitarist and singer John Maus, who was already using the stage name John Walker as a fake ID to enable him to perform in clubs while under age. At first they formed a new band, Judy and the Gents, backing John Walker’s sister Judy Maus, before joining other musicians to tour as the Surfaris (although they did not play on the Surfaris’ records). In early 1964, Scott Engel and John Walker began working together as the Walker Brothers, later in the year linking up with drummer Gary Leeds whose father financed the trio’s first trip to the UK.

As a trio, the Walker Brothers cultivated a glossy-haired and handsome familial image. Prompted by Maus, each of the members took “Walker” as their stage surname. Scott continued to use the name Walker thereafter, with the brief exception of returning to his birth name for the original release of his fifth solo album Scott 4, and in songwriting credits.

Initially, John served as guitarist and main lead singer of the trio, with Gary on drums and Scott playing bass guitar and mostly singing harmony vocals. By early 1965, the group had made appearances on TV shows Hollywood A Go-Go and Shindig and had made initial recordings, but the start of their real success lay ahead of them and overseas.

While working as a session drummer, Leeds had toured the United Kingdom with P.J. Proby, and persuaded both John and Scott to try their luck with him on the British pop scene. The Walker Brothers arrived in London in early 1965. Their first single, “Pretty Girls Everywhere” (with John still installed as lead singer) crept into the charts but did not place highly. Their next single, “Love Her” – with Scott’s deeper baritone in the lead – was a more substantial chart hit and from then on he became the group’s frontman.

The Walker Brothers’ next release, “Make It Easy on Yourself”, a Bacharach/David ballad, went to No. 1 on the UK Singles Chart (number 16 on the U.S. charts) on release in August 1965 and their second No. 1 (number 13 U.S.), “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Any More”, shot to the top in early 1966, and the Walker Brothers, especially lead singer Scott, attained pop star status.

Finding suitable material was always a problem. The Walkers’ 1960s sound mixes Phil Spector’s “wall of sound” techniques with symphonic orchestrations featuring Britain’s top musicians and arrangers, notably Ivor Raymonde. Scott served as effective co-producer of the band’s records throughout this period (alongside their named producer, Johnny Franz and engineer Peter Oliff), later described as “parallel, if invisible Walker Brothers.” Many of their earlier numbers had a driving beat, but by Images, their third album, ballads predominated.

By the time of Images, John Walker’s musical influence on the Walker Brothers had waned (although he sang lead on a cover of “Blueberry Hill” and contributed two original compositions) and this led to tensions between him and Scott. For his part, Scott was finding the group a chafing experience – “There was a lot of pressure. I was coming up with all the material for the boys, and I was having to find songs and getting the sessions together. Everyone relied on me, and it just got on top of me. I think I just got irritated with it all.”

Artistic differences and the stresses of overwhelming pop stardom led to the break-up of the Walker Brothers in 1967, although they reunited briefly for a tour of Japan the following year.

For his solo career, Scott Walker shed the Walker Brothers’ mantle and worked in a style clearly glimpsed on Images. Initially, this led to a continuation of his previous band’s success. Walker’s first four albums, titled Scott (1967), Scott 2 (1968), Scott 3 (1969), and Scott: Scott Walker Sings Songs from his TV Series (1969), all sold in large numbers, with Scott 2 topping the British charts.

During this period, Walker combined his earlier teen appeal with a darker, more idiosyncratic approach (which had been hinted at in songs like “Orpheus” on the Images album). While his vocal style remained consistent with the Walker Brothers, he now drove a fine line between classic ballads, Broadway hits and his own compositions, and also included risqué recordings of Jacques Brel songs. Walker’s own original songs of this period were influenced by Brel and Léo Ferré as he explored European musical roots while expressing his own American experience and reaching a new maturity as a recording artist.

Walker’s own relationship with fame, and the concentrated attention which it brought to him, remained a problem as regards his emotional well-being. He became reclusive and somewhat distanced from his audience. In 1968 he threw himself into intense study of contemporary and classical music, which included a time in Quarr Abbey, a monastery on the Isle of Wight, to study Gregorian chant, building on an interest in lieder and classical musical modes.

At the peak of his fame in 1969, Scott Walker was given his own BBC TV series, Scott, featuring solo Walker performances of ballads, big band standards, Brel songs and his own compositions. Footage of the show is currently very rare as recordings were not archived.

In interviews, Walker had suggested that by the time of his third solo LP, a self-indulgent complacency had crept into his choice of material. His fourth solo album – Scott: Scott Walker Sings Songs from his TV Series – exemplified the problems he was having in failing to balance his own creative work with the demands of the entertainment industry and of his manager Maurice King, who seemed determined to turn him into a new Andy Williams or Frank Sinatra.

After parting company with King, Walker released his fifth solo LP – Scott 4 – in 1969. Compensating for his recent dip into passivity, this was his first record to be made up entirely of self-penned material. The album failed to chart and was deleted soon after. It has been speculated that Scott Walker’s decision to release the album under his birth name of Noel Scott Engel contributed to its chart failure. All subsequent re-issues of the album have been released under his stage name.

The Walker Brothers reunited in 1975 to produce three albums. Their first single, a cover of Tom Rush’s song “No Regrets”, from the album of the same title climbed to number 7 in the UK Singles Chart. However, the parent album only reached number 49 in the UK Albums Chart. The two singles from the next album Lines (its title track, which Scott regarded as the best single the group ever released, and “We’re All Alone”) both failed to chart, and the album fared no better.

With the imminent demise of their record label, the Walkers collaborated on an album of original material that was in stark contrast to the country-flavoured tunes of the previous 1970s albums. The resulting album, Nite Flights, was released in 1978 with each of the Brothers writing and singing their own compositions. The opening four songs were Scott’s, the final four John’s, while the middle pair were by Gary. The extremely dark and discomforting sound of Scott’s songs, particularly “The Electrician”, was to prove a forerunner to the direction of his future solo work.

In spite of a warm critical reception (with his contributions particularly lauded), sales figures for Nite Flights were ultimately as poor as those of Lines. The supporting tour saw the band concentrating on the old hits and ballads and ignoring the songs from their new record. Apparently now fated for a stagnant career on the revival circuit, the Walker Brothers lost heart and interest, compounded by Scott’s increasing reluctance to sing live. By the end of 1978, now without a record deal, the group drifted apart again and Scott Walker entered a three-year period of obscurity and no releases.

In 1981, interest in Scott Walker’s work was stimulated by the compilation Fire Escape in the Sky: The Godlike Genius of Scott Walker, containing tracks selected by Julian Cope, which reached number 14 on the UK Independent Chart. Walker subsequently signed with Virgin Records.

In 1984, Scott Walker released his first solo album in ten years, Climate of Hunter. The album furthered the complex and unnerving approach Walker had established on Nite Flights. While based loosely within the field of 1980s rock music (and featuring guest appearances by contemporary stars Billy Ocean and Mark Knopfler), it had a fragmented and trance-like approach. Many of its eight songs lacked either titles or easily identifiable melody, with only Walker’s sonorous voice as the link to previous work.

Like Nite Flights before it, Climate of Hunter was met with critical praise but low sales. Plans to tour were made but never came to fruition. A second album for Virgin was rumoured to be in the works (with Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois producing) but was abandoned after early sessions and soon after Walker was dropped by the label.

Walker spent the late 1980s away from music, with only a brief cameo appearance in a 1987 Britvic TV advert (alongside other 1960s pop icons) to maintain his profile. He did not return to public attention until the early 1990s when his solo and Walker Brothers work was critically reappraised again.

During this period Walker’s first four studio albums were issued on CD for the first time and the compilation album No Regrets – The Best of Scott Walker and The Walker Brothers 1965–1976 hit number 4 on the UK Albums Chart. Walker’s own return to current active work was gradual and cautious.

In 1992 he co-wrote and co-performed (with Goran Bregović) the single “Man From Reno” for the soundtrack of the film Toxic Affair. Having signed to Fontana Records, he began work on a new album. In the meantime David Bowie covered Scott’s song “Nite Flights” on his Black Tie White Noise album, which also contained the Walker inspired ‘You’ve Been Around’.

Tilt was released in 1995, developing and expanding the working methods explored on Climate of Hunter. Variously described as “an anti-matter collision of rock and modern classical music”, as “Samuel Beckett at La Scala” and as “indescribably barren and unutterably bleak… the wind that buffets the gothic cathedrals of everyone’s favorite nightmares”, it was more consciously avant-garde than its predecessor with Walker now revealed as a fully-fledged modernist composer.

Although Walker was backed by a full orchestra again, this time he was also accompanied by alarming percussion and industrial effects; and while album opener “Farmer in the City” was a melodic piece on which Walker exercised his familiar ballad voice, the remaining pieces were harsh and demandingly avant-garde.

In 1996, Scott Walker recorded the Bob Dylan song “I Threw It All Away” under the direction of Nick Cave for inclusion in the soundtrack for the film To Have and to Hold. In 1998, in a rare return to straightforward balladeering, he recorded the David Arnold song “Only Myself to Blame” (for the soundtrack of the Bond film The World Is Not Enough) and also wrote and produced the soundtrack for the Léos Carax film Pola X, which was released as an album.

In 2000, Walker curated the London South Bank Centre’s annual summer live music festival, Meltdown, which has a tradition of celebrity curators. He did not perform at Meltdown himself, but wrote the music for the Richard Alston Dance Project item Thimblerigging. The following year he served as producer on Pulp’s 2001 album We Love Life (whose track “Bad Cover Version” includes a mocking reference to the poor quality of “the second side of ‘Til The Band Comes In”).

In October 2003, Walker was given an award for his contribution to music by Q magazine, presented by Jarvis Cocker of Pulp. Walker received a standing ovation at the presentation. This award had been presented only twice before, the first time to Phil Spector, and the second to Brian Eno.

On May 8, 2006, Scott Walker released The Drift, his first new album in 11 years.

In June 2006, Mojo and radio honored Scott Walker with the MOJO Icon Award: “Voted for by Mojo readers and Mojo4music users, the recipient of this award has enjoyed a spectacular career on a global scale”. A documentary film, Scott Walker: 30 Century Man, was completed in 2006 by New York film director Stephen Kijak (Cinemania and Never Met Picasso).

Interviews were recorded with David Bowie (executive producer of the film), Radiohead, Sting, Gavin Friday and many musicians associated with Walker over the years. The World Premiere of Scott Walker: 30 Century Man took place as part of the 50th London Film Festival. When The Independent released its list of “Ten must-see films” at the 50th London Film Festival, Scott Walker: 30 Century Man, was among them.

On September 24, 2007, Walker released And Who Shall Go to the Ball? And What Shall Go to the Ball? as a limited editions. The 24-minute instrumental work was performed by the London Sinfonietta with solo cellist Philip Sheppard as music to a performance by London-based CandoCo Dance Company.

Walker’s final solo album, Bish Bosch, was released on December 3, 2012 and was received with wide critical acclaim.

In 2014, Walker collaborated with experimental drone metal duo Sunn O))) on a new album. The album, Soused, was released on October 21, 2014.

Scott Walker died at the age of 76 in London on March 22, 2019. His death was announced three days later by his record company who called him “a unique and challenging titan at the forefront of British music”.

Check out Scott Walker on Amazon

Check out The Walker Brothers on Amazon

If you found this article interesting, please share it with your friends and family, and why not check out our article on other Musicians who died in 2019.

.

Pingback: Burt Bacharach, probably pop's greatest songwriter, died February 08, 2023 - Dead Musicians

Pingback: Tim Buckley died June 29, 1975 - Dead Musicians